About social vulnerability to natural hazards and climate-related hazards

This section presents information about population social vulnerability to natural hazards and climate-related hazards. It explains the different dimensions of social vulnerability, and why they are important.

On this page:

Some people are more vulnerable to impacts of natural hazards and climate-related hazards

Some people are more vulnerable to the negative impacts of natural hazards and climate change, due to their current circumstances.

Understanding the vulnerability of a population or community can help identify the specific needs of that population. This can help improve resilience through informing disaster risk reduction, preparedness, response and recovery activities.

'Social vulnerability' refers to population groups who may be vulnerable to negative impacts of natural hazards or climate change on their health and wellbeing, due to pre-existing conditions, sociodemographic characteristics and circumstances.

Negative impacts of natural hazards and climate-related hazards on people’s health and wellbeing may include:

- injuries and/or death

- illness (eg due to contact with contaminated water)

- worsening of existing health conditions (such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma)

- poorer mental health

- damage to houses and property

- disruption to lifeline infrastructure (such as roading, power, water supplies, telecommunications)

- displacement and disruption to livelihoods.

Vulnerable populations will be more impacted by the negative health impacts of natural hazards and climate change. For example, vulnerable populations may:

- be susceptible to the impacts because of their age or pre-existing health conditions

- have limited resources or capacities to prepare for or cope with a crisis or emergency

- struggle to recover after an event

- have difficulty moving themselves out of harm’s way during an event

- find it difficult to adapt longer-term to climate-related hazards.

Social vulnerability and climate change

Climate change will increase the frequency and severity of climate-related hazards in New Zealand [2]. Climate-related hazards include floods, extreme storm events, heatwaves, drought, wildfire, and sea level rise. Climate change can also have an indirect effect on a population’s health (eg through water quality, air quality, vector-borne diseases, and food security).

Vulnerable people will be disproportionately affected by climate change [1]. Climate impacts and risks may also exacerbate existing vulnerabilities and inequities [1].

Understanding vulnerability is vitally important for informing adaptation planning for climate change. Reducing vulnerability is a key component of improving resilience and adapting to climate change [1,3].

Dimensions of social vulnerability

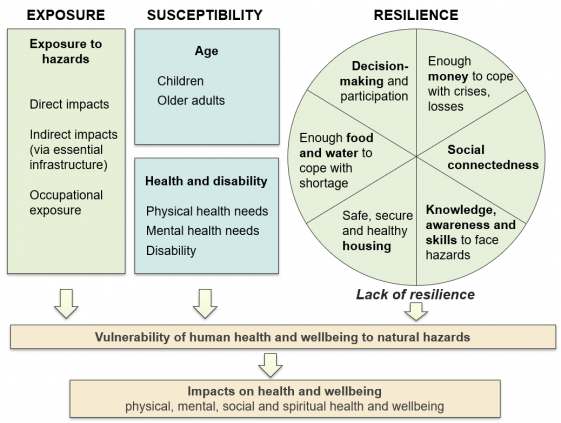

Social vulnerability is influenced by the following [4]:

- Exposure: being exposed to the hazard (such as flood hazards)

- Susceptibility: being more susceptible or sensitive to the impacts of the hazard

- Lack of resilience: relating to the capacity to prepare for, cope with, recover from and/or adapt to a hazard.

Figure 1 shows the EHINZ conceptual framework for social vulnerability to natural hazards and climate change. This framework gives a structured way of thinking about social vulnerability to natural hazards and climate change.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework for social vulnerability to natural hazards [5]

Note: This framework is based on the MOVE framework for assessing vulnerability to natural hazards and climate change [4]. It also includes key elements of resilience from the Circle of Capacities [6] and health and wellbeing from Te Whare Tapa Whā - Māori model of health and wellbeing [7]. It is consistent with the IPCC approach that climate risk is influenced by the hazard, exposure, sensitivity/susceptibility to harm, and lack of capacity to cope and adapt [1].

This framework was used to inform the selection of social vulnerability indicators.

Measuring vulnerability with social vulnerability indicators

EHINZ has developed the first suite of social vulnerability indicators (SVIs) for natural hazards and climate change for New Zealand, nationally and locally.

Social vulnerability indicators are a useful tool for understanding social vulnerability in a community. These indicators identify different aspects that contribute to vulnerability.

Social vulnerability indicators identify geographic areas where people are more vulnerable to these negative impacts of natural hazards (including climate change). In these areas, people may be less able to anticipate, prepare, cope and recover from an event.

Understanding the vulnerability of a population can identify the specific needs of that population. This can help improve resilience through informing disaster risk reduction, preparedness, response and recovery activities. Understanding vulnerability is also vitally important for informing adaptation planning for climate change.

To explore the latest social vulnerability indicators, see the Social vulnerability indicators for 2023.

Who is more vulnerable? Rationale for the social vulnerability indicators

The social vulnerability indicators cover the following dimensions:

- Population

- Children and young people

- Older adults

- Health and disability status

- Having enough money to cope with crises and losses

- Social connectedness

- Awareness, skills and knowledge to cope with hazards

- Safe, secure and healthy housing

- Having enough food and water to cope with shortage

- Decision-making and leadership

- Occupational exposure/vulnerability

- Other individual-level factors of social vulnerability.

This section explains these different dimensions of social vulnerability, and why they are important.

Population

Understanding the number of people exposed to a hazard can help national and local authorities to develop their emergency plans and responses.

Areas of higher population density may be more vulnerable, because more people are affected in a smaller land area.

People in rural areas may also be vulnerable. They are more likely to be cut off during or after an event. During these events, people in rural areas may have difficulty accessing services. They may experience disruptions to power, telecommunications, and water supplies.

Vulnerability may also differentially affect ethnic groups. Understanding the ethnic diversity of the population can help to tailor services and meet the needs of the local community. Māori are tangata whenua, and they play an important role in building resilience and informing emergency response.

Children and young people

Children and young people are vulnerable to the impacts of natural hazards and emergencies. They often need to rely on adult caregivers to protect them from hazards. Children may find it difficult to recognise a hazard and react to it.

Children may also be more susceptible to some health impacts, as their bodies and immune systems are still developing.

Older adults

Older adults are also more vulnerable to the impacts of natural hazards and emergencies. They generally have high levels of pre-existing health conditions, such as coronary heart disease and diabetes. They are more likely to have hearing or vision loss, and they tend to be less mobile. They may also have limited social networks and be socially isolated, particularly if they live alone.

Health and disability status

People with health needs may be more susceptible to health impacts in a natural hazard event or emergency. For example:

- People with pre-existing health conditions may be more susceptible to illness or other health problems (eg heart attack). Certain health conditions may make people more susceptible, including: coronary heart disease, respiratory conditions, diabetes.

- People with mental health issues are more susceptible to health impacts. They may be particularly susceptible to the impacts of stress, social isolation and financial difficulties.

- People who need access to healthcare services and/or essential medications may struggle to access these.

- Pregnant women may be at increased risk due to decreased immunity.

- People with disabilities may rely on caregivers to help them.

Having enough money to cope with crises and losses

An important aspect of resilience is having enough money to cope with crises or losses resulting from a disaster or event.

People or households with low incomes may not have the money to cope with sudden crises or losses. They may not have money to protect themselves, eg through insurance, flood protection works, or having emergency supplies. These people are particularly vulnerable to job losses and decreases in income.

During and after an event, households without access to a car may be more vulnerable. These households may find it difficult to move out of hazard zones in a hurry, or to access important services.

Social connectedness

Having strong social connections makes people more resilient during and after a natural hazard event or emergency. People are able to help and support each other, particularly when they know other people in the community.

By contrast, not knowing other people, or being socially isolated, can increase a person's vulnerability. People who are socially isolated may not have other people to help them when needed. People who are new to the country or neighbourhood may not have strong social connections to people in their neighbourhood. People living alone (particularly older adults living alone) may not have other people close by to help them during an event.

Awareness, knowledge and skills to cope with hazards and emergencies

People who do not know about local hazards are more vulnerable during an event. Also, being able to understand information, and act on recommendations, is important during an emergency. It enables people to prepare, understand official advice, and know where to seek help and access services.

Having internet and phone access is important for accessing information. Internet and phone access are also alternative methods of accessing health services (eg telemedicine).

Some people may have difficulty understanding and/or accessing information and services. These groups include people who do not speak English, who are new to the country, or who have low literacy levels. These people may also not know about local hazards.

Safe, secure and healthy housing

Having safe, secure and healthy housing is very important. Shelter, warmth and security are some of the basic needs for human survival. People can spend a lot of time at their house, so poor housing can impact health and wellbeing.

Crowded households lead to many people in a house, relative to the number of bedrooms. Crowded houses can put pressure on emergency resources in a household. Household crowding also increases the risk of infectious diseases.

Cold, damp and mouldy houses are unhealthy for people's health. They can worsen asthma symptoms, and may increase the risk of asthma development and respiratory tract infections.

Rental housing is less secure for tenants. Rental housing has also generally been of poorer quality than other houses in New Zealand.

Enough food and water to cope with shortage

Having enough safe food and water is essential for survival, and is a basic human need. People's health and wellbeing can be affected during an event if they don't have enough food or water. A power supply can be important to keep fridges and freezers running. Having a way to cook food is also important.

Some people may also not be able to afford sufficient food, which can cause vulnerability. In New Zealand, some population groups are more likely to be food insecure (ie not have access to safe, nutritious and affordable food) [8]. Similar population groups may not be able to meet emergency preparedness requirements [9]. These groups are more vulnerable, and include:

- people living in rental housing

- people living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation

- people with low household incomes

- single-parent families.

Decision-making ability and participation

Good leadership and decision-making (at the personal, local, regional and national level) is vitally important during and after a natural hazard or other emergency.

Additionally, people's ability to participate in and influence decision-making is important for resilience. People need to feel like they have control over their situation, for example being able to access information when they need it.

People also need to be able to participate in decision-making processes at the community and government level. This helps to build resilience in local communities, and ensures that decisions can be made to meet people's needs.

People left out of the decision-making process may feel that their needs have not been listened to or fully met, and will be more vulnerable. In particular, including local iwi/hapū and vulnerable population groups (such as people with disabilities) in decision-making helps to build resilience in these groups.

Occupational exposure / vulnerability

People's occupational exposure and/or vulnerability depends on the natural hazard or emergency.

Healthcare workers and first responders may treat patients affected by an event. This may put them at higher risk, as they are more likely to be exposed to the hazard. They are also more likely to experience psychosocial impacts, stress and/or burnout.

People working in the primary industries may be more vulnerable to floods, droughts and wildfires. These types of hazards can affect agriculture, the well-being of animals, and production of food. These hazards can affect livelihoods and food security, as well as the mental health of people affected.

Other individual-level factors of social vulnerability

Other potentially vulnerable population groups include:

- People in institutions (such as prisons), who may rely on others to look after them during an event

- People living in other types of group quarters (such as university dorms, military quarters, rest homes)

- People who own or look after animals (such as pets or livestock), as they may put their safety at risk to try to rescue their animals

- People who have previously experienced domestic violence, as this is a key contributor to experiencing domestic violence again after a natural hazard.

For more information about the rationale for the indicators, see Mason et al (2021) [5], the ![]() Research report (pdf, 3.6MB) and the

Research report (pdf, 3.6MB) and the ![]() Rationale, indicators and potential uses report (pdf, 981KB). Further rationale for social vulnerability to climate change is also available in Li et al (2023) [10].

Rationale, indicators and potential uses report (pdf, 981KB). Further rationale for social vulnerability to climate change is also available in Li et al (2023) [10].

To explore the latest social vulnerability indicators, see Social vulnerability indicators for 2023.

References

1. IPCC. 2023. Summary for Policymakers, in Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

2. Ministry for the Environment. 2016. Climate Change Projections for New Zealand. Atmospheric projections based on simulations undertaken for the IPCC 5th Assessment. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

3. Birkmann J, Feldmeyer D, McMillan JM, et al. 2021. Regional clusters of vulnerability show the need for transboundary cooperation. Environmental Research Letters 16: 094052.

4. Birkmann J, Cardona OD, Carrenoet ML, et al. 2013. Framing vulnerability, risk and societal responses: the MOVE framework. Natural Hazards, 67(2): 193-211.

5. Mason K, Lindberg K, Haenfling C, et al. 2021. Social vulnerability indicators for flooding in Aotearoa New Zealand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(8): 3952. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18083952

6. Wisner B, Gaillard J, Kelman I. 2012. Framing disaster: Theories and stories seeking to understand hazards, vulnerability and risk, in Handbook of Hazards and Disaster Risk Reduction, Wisner B, Gaillard J, Kelman I (eds). Routledge: London.

7. Durie M. 1985. A Māori perspective of health. Social Science & Medicine 20(5): 483-486.

8. Ministry of Health. 2019. Household Food Insecurity Among Children in New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

9. Statistics New Zealand. 2012. How prepared are New Zealanders for a natural disaster? Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

10. Li A, Toll M, Bentley R. 2023. Mapping social vulnerability indicators to understand the health impacts of climate change: a scoping review. Lancet Planet Health 7: e925-37.